In her landmark book Longitude, Dava Sobel provided an inspiring history of the need for, and development of the machines that allowed sailors to finally measure time with the reliability needed to ascertain with some accuracy, their position east or west in order to map their discoveries of new lands.

Travelers have always relied on gear to make their treks efficient, comfortable and safe. Archaeologists have volumes of stories about discoveries of the remains of ancient peoples, where, in addition to the bones, they found primitive alidades and transits for navigating among landmarks. Thousands of years ago, Pacific island peoples developed wonderful and elegant tools to assess the wind and waves to ensure they were going the right direction.

Years ago, when I was working for the Oceanographer of the Navy, we learned that there was a crisis brewing in the fleet, around the loss of skills for navigation. The gear had advanced, but the knowledge and training of the systems hadn’t kept up. In one case, a large Navy ship ran aground overseas (and, no kidding, the official Naval message read “WE HAVE HIT THE CONTINENT”) because the ship’s navigation system had not been set for the appropriate datum, that is, the reference for GPS in any particular area. In another infamous case, a grounded Naval aviator, who had ditched behind enemy lines, knew that he had to determine his location, but feared that if he turned on his GPS it would inadvertently transmit his location to the enemy; he was unaware that the GPS was only a receiver. At that point, the Oceanographer of the Navy (RADM Dick West … a real ‘sailor’s sailor’) initiated a major effort to re-educate Naval forces on navigation principles.

So, what’s my point? Well, it’s about having the right gear and knowing how to use it. Now, I don’t expect to be so lost that I can’t tell east from west, and, unless this year’s Presidential election really gets out of hand, I don’t expect to find myself behind enemy lines, but I do like the idea of having some state-of-the-art tools to make my walk, well … efficient, comfortable and safe! Consequently, I’ve spent the better part of two years assessing what’s out there, and testing, rejecting and selecting the kit that best suits my needs, and assuages my concerns.

Here we go …

WARNING TO THE READER: There’s a pretty high geek factor in the rest of this blog, so I fully understand if some readers simply hit “ESCAPE” at this point. But for those of you with an interest, here goes.

The route I’ve planned is a real hybrid of roads and trails. Robert Moor wrote in his wonderful book On Trails that trails don’t just arise randomly, but are the result of an intelligence passed from one generation to another, or even from one species to another. Would that I could count on such wisdom of those who went before me, but the fact of the matter is that there really is not a lot of collective knowledge regarding the best route for walking from Delaware to Oregon. The American Discovery Trail (http://www.discoverytrail.org) is a fine collective characterization of how to walk to Southern California from the East Coast. But, not much interested in a 1500 mile detour from my designated designation, I learned that I needed to define my full route myself. For that, I turned to authoritative sources such as Google Earth, and the Rails-To-Trails Conservancy (RTC, http://www.railstotrails.org). The former, of course, is the quintessential geographic information system for the masses. The RTC is a great group who’ve worked tirelessly to pass laws and raise funds for converting old railroad tracks into trails. I started planning the route by doing the most logical thing any traveler should do: draw a Great Circle. I figured if I could adhere closely to a Great Circle route between Delaware and Oregon I’d be minimizing unnecessary wandering. With that wonderful arc plotted (and, of course passing through lakes, over mountains and across superhighways) I then used RTC on-line resources and Google Maps to find the closest paths, trails, and byroads, and proceeded to lay out 51 legs of blazed paths to define the 3154 mile route. With the route established, I needed to make sure that: 1) I stayed on the route, and ; 2) my friends and family could access the route and know where I was on it at any given time.

In simple terms, this meant that I needed to be able to navigate, track/situational awareness, and communicate.

• Navigation = Plotting the route

• Tracking/SA = Following that route … and knowing that I’m following that route

• Communication = Letting others know I’m on the route.

That’s where we get into the cool gizmos.

I have three critical tools that I’ll keep with me at all times: my iPhone 6S, a Garmin EPIX, and a DeLorme InReach Explorer :

iPhone 6S with the GPS Tracks app (http://gpstracksapp.com)– for navigation

Once I determined the optimal route – by using the Rails-to-Trails extensive database of trails, along with Google Maps application providing walking directions – I saved each leg of TLWH as a file (.kml, or .gpx, or .kmz format) in my iCloud account, and can export it to the GPS Tracks app on my iPhone. That gives me a very clear, and highly resolved track to follow to get to and from each pre-planned waypoint on the walk. I’ll always be able to confirm whether I’m on track or veering into uncharted territory. This app also has a very nice set of track statistics that it acquires as you walk (pace, elevation gain, etc.). Additionally – and this is a really nice feature – the app automatically sends the tracked route to both an iCloud and DropBox account. That means I never need to worry about archiving the route. When I want to look back at where I walked, five minutes after I’ve passed, or ten years from now, I’ll have the route permanently stored in the cloud. The only problem with this system is that it requires me to take out the iPhone every time I need guidance… Not a problem in Nebraska, where I’ll basically be walking straight for 300 miles, or on clear trails like the GAP in Pennsylvania, but there are some legs that require navigational adjustments every 3 or 4 miles. That’s where the tracking and communication come in.

GARMIN EPIX watch (https://buy.garmin.com/en-US/US/into-sports/hiking/epix-/prod146065.html) – for tracking and sustained situational awareness

As of mid-2016 this watch was the only wearable GPS device with full real-time mapping capacity. And, it’s linkable (via Bluetooth) to my iPhone. So, now, that same track that I saved into the GPS Tracks app can also be loaded onto the EPIX. That way, on any given leg, all I need do is check my wristwatch to see if I’m still on track. It’s also got some cool widgets, such as a weather tool that will warn me when there’s a storm warning within 30 minutes of my predicted track. It’ll also, apparently, measure my pulse and blood pressure if I so desire, but somehow I don’t think that will be something I want to necessarily know. Although, I suspect the local medical examiner could use that information when they find my body beside some steep trail side and need to assess cause of death! But before they ever find me, I’ll need to have a way to communicate my position and status. That’s where the coolest gadget comes in …

DeLorme InReach Explorer (http://www.inreachdelorme.com/product-info/inreach-explorer.php?gclid=CPLE0cex788CFY1bhgodiEoFbA) – for communication

This is a hybrid GPS receiver, with an Iridium communicator. It transmits my exact position continuously, at frequencies as high as every two minutes. These data are sent via the Iridium satellite communications network. This is important, since it will work anywhere in the world, anytime. I know, because I tested it last year in the Antarctic. I kept – somewhere in my files – a transmission showing my position as -89.999 degrees South, when I was standing at the exact South Pole. The positions can be sent to anyone I’d like, via text, or Facebook, or to a password-controlled website with a mapping feature. Perhaps even more important, this nifty little device can transmit and receive text messages – again, from anywhere in the world. That, coupled with an SOS feature, adds a nice element of security. In short, the Explorer is my tether to the rest of the world.

There are some other cool devices that I’ll include. Perhaps the cleverest is my GoTenna (http://www.gotenna.com/).  The last mile of communication is often the most important. The DeLorme Explorer will allow me to tell others where I am within the error circle of GPS, but what if the folks I’m trying to communicate with have only cell phones, and don’t happen to be walking around with an Iridium satellite phone? Well, the smart folks at a startup called GoTenna, realizing that even without cell towers around, our cell phones are still powerful transmitters/receivers. They’ve produced a Bluetooth-linkable antenna that basically converts your phone into a texting walkie-talkie, even where there’s no cell coverage. If you and a partner have matched GoTenna antennae (about the size of a fountain pen) you can communication over a couple of miles. So … when Alanna and I are trying to communicate at the end of the day in the wilds of Wyoming, no problem. Just start texting with the GoTenna, and we’re connected.

The last mile of communication is often the most important. The DeLorme Explorer will allow me to tell others where I am within the error circle of GPS, but what if the folks I’m trying to communicate with have only cell phones, and don’t happen to be walking around with an Iridium satellite phone? Well, the smart folks at a startup called GoTenna, realizing that even without cell towers around, our cell phones are still powerful transmitters/receivers. They’ve produced a Bluetooth-linkable antenna that basically converts your phone into a texting walkie-talkie, even where there’s no cell coverage. If you and a partner have matched GoTenna antennae (about the size of a fountain pen) you can communication over a couple of miles. So … when Alanna and I are trying to communicate at the end of the day in the wilds of Wyoming, no problem. Just start texting with the GoTenna, and we’re connected.

Other stuff

That’s it for the unique high tech gear. Of course I’ll have a good camera, a Nikon Coolpix S9900, which automatically tags my photos not just with date, but also GPS location, and compass orientation. I’ll make sure all the best photos end up on this blog.

I also carry the usual stuff that every good hiker carries. My package includes:

• REI Flash 22L pack – I can’t even tell I’m carrying this thing. I’ve spent more time with this pack over the last two years than I have with Alanna.

• Fitbit – I’m figuring I’ll add about 6.5M steps to my tally – what’s the badge for that?

• Footwear – Silk liners, Smartwool heavy duty hiking socks, custom-designed orthotics, and Keen Targhee II hiking shoes. Ain’t nobody happy if the dogs ain’t happy

• Lots of other small stuff – headlamp, cooling bandanna, packable down coat, packable rainwear, pepper spray, whistle, etc.

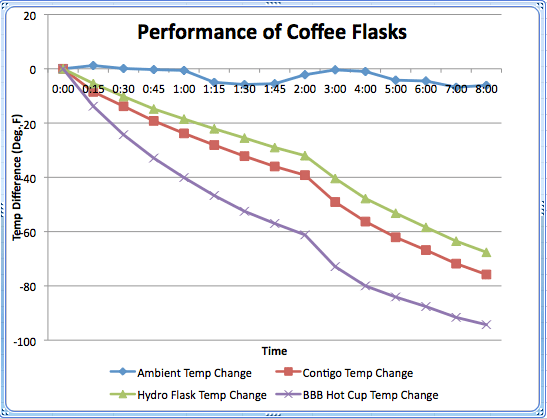

Before I close out this posting, however, I need to go back to a comment made in an earlier blog. Last year, after finishing the C&O Canal, I listed some lessons learned, including one, where I said that no flask has been invented that will keep coffee warm all day. Well, recently, my co-worker and friend, Emily Larkin, told me I was wrong, and that Hydro Flasks (http://www.hydroflask.com) would do that. So, having a few hours to kill on a recent Saturday, I did an experiment. Here are the results.

So, I owe Emily an apology. Hydro Flask did outperform what I thought was the best coffee flask on the market. You will note that this experiment was clearly done under highly controlled conditions, and while I’m not sure my kitchen adheres to ISO9000 standards, it’s still pretty clear the Hydro Flask will now be my coffee thermos of choice! Can’t wait to test it on the trail.

Any endeavor requiring gear is worthy. Be safe and enjoy every step.

LikeLike

I’m a bit behind on commenting, but I have to say, I’m happy that the Hydroflask lived up to my promises. I hike with mine in the summer, too – just with iced tea instead of coffee.

LikeLike